Posted item #3 Notes on democratic centralism (June 1968)

Posted item #3 Notes on democratic centralism (June 1968)1968 was a momentous year: student occupations, mass strikes, anti-war demonstrations, riots, and much more. Although France is the country firmly lodged in popular consciousness, '68 saw social and political upheavals in most regions of the world. And while many people know it as the year of student unrest, it was the French general strike that marked the peak of struggle in western Europe.

Here in Britain there wasn't the scale of rebellion seen in some places, yet it was still the high point of the movement against war in Vietnam, a crucial year for student sit-ins and protests, and a time of ideological ferment. It is revealing that the International Socialists (forerunner of the SWP) went from just 400 members at the start of the year to around 1000 members in December 1968.

It was in Decemeber 1968 that IS held a conference which crystallised a sense of crisis inside the organisation. This might be surprising, but such sudden growth is likely to generate serious tensions. Some of the more experienced comrades - many of whom had in fact been members for no more than a few years themselves - felt undermined by the new influx or were concerned that they 'diluted' the revolutionary Marxist politics of IS. The new members, meanwhile, came from a variety of backgrounds politically and were subject to a range of ideological presures and influences. Towards the end of 1968 there were several factions, however short-lived, inside the organisation.

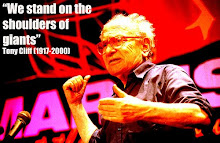

Three things reflect Tony Cliff's qualities as a revolutionary and a leading figure in IS from this turbulent time. First, he developed - extremely swiftly - a highly perceptive response to the French events and the broader sweep of revolt internationally. He recognised, for example, the vital role of students as detonators of mass struggle, while resisting the common tendency in 1968 to laud students as a 'new vanguard'. Cliff instead argued that the organised working class remained indispensable and central to effecting social change. His pamphlet 'France - the struggle goes on', co-written with Ian Birchall, was a crucial contribution to understanding the complex dynamics of the French events.

Secondly, he gave a lead in orienting IS on the new struggles taking place and the charged political atmosphere among students. He spent weeks going to the London School of Economics - epicentre of student revolt in Britain - and argued with students about the political issues being thrown up by the global rebellion. He led by example, winning a layer of students to revolutionary socialist ideas. While consistent in saying that students couldn't substitute for workers in making a revolution, he realised that newly radicalised students could play an important role in strengthening IS and the wider Left.

Finally, Cliff managed to navigate the stormy waters of his organisation's own internal crisis. He intervened in important conferences in September and Decemeber 1968, and sought to explain to new recruits - disillusioned with the setbacks that quickly accompanied the breakthroughs of '68 - the need for on-going and patient work in building socialist organisation. He was also willing to challenge the conservatism of many of the more experienced members, struggling to adjust to radically changed circumstances.

His key intervention, in writing, was a very short article 'Notes on democratic centralism'. This seems quite technical, but in fact reflects a fundamental concern with kind of organisation Cliff thought revolutionaries needed to build. It implicitly took on arguments within IS, especially from those of a more 'liberterian' bent.

IS had until then been organisationally loose, which meant that striving for a tighter, more cohesive force challenged the habits and assumptions of many established members. But it was also contentious with many new members, who were inclined - in the heady atmosphere of '68 - to privilege 'spontaneity' and downplay the kind of patient work and orientation on working class organisation required in the long term.

Cliff's arguments for democratic centralism, though rushed and under-developed, helped IS get through a brief period of crisis and sustain itself beyond the dramatic events of 1968. They also laid the basis for building effective revolutionary organisation in the 1970s - and indicated Cliff's preoccupation in those years with how to build a revolutionary party. This found its flowering mainly in the numerous articles about Lenin and the first volume of Cliff's Lenin biography, which centred on the great revolutionary's efforts to build the Bolshevik Party.

Further reading: Ian Birchall's article on Cliff in 1968

No comments:

Post a Comment