My previous post concerned Socialist Worker, especially in the upturn years of 1968-74, as an illustration of the role of a newspaper in building socialist organisation. This included my final link to one of Tony Cliff's own articles, but I think it's also useful to read Ian Birchall's account of this period. There's a great deal of overlap with Cliff's 1974 article about Socialist Worker; as a historical summary, focusing especially on how the International Socialists (forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party) responded to the times, it provides all the relevant background.

As well as illuminating this hugely important era in the history of the left and the working class movement in Britain, Birchall's essay also offers some fascinating insights into how a revolutionary socialist organisation can grow. IS had 400+ members at the start of 1968; by 1974 it had over 3000. There was no weekly paper at the start of 1968; by 1974 a 16-page weekly Socialist Worker peaked at a circulation of 40,000. The journey was uneven and dotted with obstacles, but it remains a superb achievement for such a small group to make so much of the possibilities - and reap the benefits.

Thursday, 27 August 2009

Wednesday, 26 August 2009

The revolutionary paper as organiser

Posted item #16 'The use of Socialist Worker as an organiser'

This is the final example of Cliff's writing that I am posting. Looking back over this blog, as it's developed during the last few weeks, I'm conscious of the wide range of topics covered. However, even this range doesn't fully reflect the breadth of Cliff's political expertise, which can be more fully grasped by referring to the Cliff index on the Marxists Internet Archive.

This is an appropriate place to conclude the archive of Cliff's own work: an article about the revolutionary paper, one of Cliff's abiding preoccupations. The paper was central to his conception of a revolutionary party and its work, a commitment inherited directly from Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who famously published Pravda (a daily paper launched in 1912).

The article's title sums up the newspaper's political significance for Cliff, as for Lenin: not merely propaganda, the paper serves practical organisation by revolutionary socialists. It is published by the party and is accountable to it. It is, above all, a method for creating networks of socialists, and furthermore enabling those organised socialists to connect with wider layers of sympathisers and supporters.

Cliff took from his knowledge of Pravda, which he wrote about in the first volume of his Lenin biography (published in 1975), the notion of a workers' paper not just a paper for workers, i.e. workers must have a sense of ownership of the paper, which derives from it being partly composed of workers' own contributions and also from selling the paper. When someone moves from buying to selling a publication something important changes - they identify themselves with it, and with its political ideas and the organisation created through its networks.

Socialist Worker was launched as a weekly in September 1968 (previously there had been a monthly paper). It was just a scruffy 4 pages, but this increased to 6, then 8, then 12, and finally 16 pages by 1972. This rapid growth in the paper's size, during just a few years, was accompanied by similarly rapid growth in circulation. In 1972 the International Socialists (IS) only had between 2000 and 3000 members, yet the paper's circulation was around 30,000, providing the relatively small organisation with a wide periphery.

Sales are thought to have peaked in 1974, with circulation reaching 40,000, on the back of a period of upturn in working class combativity and struggle. This article was published in April 1974, when socialists and the labour movement were still riding high on the crest of the wave of workers' militancy, in an internal bulletin for members of IS.

This is the final example of Cliff's writing that I am posting. Looking back over this blog, as it's developed during the last few weeks, I'm conscious of the wide range of topics covered. However, even this range doesn't fully reflect the breadth of Cliff's political expertise, which can be more fully grasped by referring to the Cliff index on the Marxists Internet Archive.

This is an appropriate place to conclude the archive of Cliff's own work: an article about the revolutionary paper, one of Cliff's abiding preoccupations. The paper was central to his conception of a revolutionary party and its work, a commitment inherited directly from Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who famously published Pravda (a daily paper launched in 1912).

The article's title sums up the newspaper's political significance for Cliff, as for Lenin: not merely propaganda, the paper serves practical organisation by revolutionary socialists. It is published by the party and is accountable to it. It is, above all, a method for creating networks of socialists, and furthermore enabling those organised socialists to connect with wider layers of sympathisers and supporters.

Cliff took from his knowledge of Pravda, which he wrote about in the first volume of his Lenin biography (published in 1975), the notion of a workers' paper not just a paper for workers, i.e. workers must have a sense of ownership of the paper, which derives from it being partly composed of workers' own contributions and also from selling the paper. When someone moves from buying to selling a publication something important changes - they identify themselves with it, and with its political ideas and the organisation created through its networks.

Socialist Worker was launched as a weekly in September 1968 (previously there had been a monthly paper). It was just a scruffy 4 pages, but this increased to 6, then 8, then 12, and finally 16 pages by 1972. This rapid growth in the paper's size, during just a few years, was accompanied by similarly rapid growth in circulation. In 1972 the International Socialists (IS) only had between 2000 and 3000 members, yet the paper's circulation was around 30,000, providing the relatively small organisation with a wide periphery.

Sales are thought to have peaked in 1974, with circulation reaching 40,000, on the back of a period of upturn in working class combativity and struggle. This article was published in April 1974, when socialists and the labour movement were still riding high on the crest of the wave of workers' militancy, in an internal bulletin for members of IS.

Monday, 24 August 2009

Midnight of the century

Posted item #15 'The Moscow Trials'

The 1930s were turbulent times and witnessed the historic defeat of the working class in two hugely important ways: the rise of fascism and the entrenchment of Stalinism in the Soviet Union. The triumph of Hitler's Nazis in 1933 represented a crushing defeat for the powerful German working class, while the consolidation of Stalin's power crushed the hopes of 1917 and nearly extinguished the authentic marxist tradition.

Trotsky, more than anyone, carried the torch of genuine revolutionary socialism forwards. He did this in extraordinarily harsh and brutal conditions, for himself personally and for his supporters.

Many of Trotsky's 1930s writing exemplify the best in the marxist tradition - for example his analysis of the events in Germany - and he strove to continue revolutionary organisation, despite awful repression in the Soviet Union (from where he was exiled in 1929) and being so marginalised everywhere.

The Moscow Trials of 1935-37 symbolise how far Stalin's counter-revolution had gone, how utterly removed from the revolutionary aspirations of the post-1917 period his regime had become. Many of the Bolsheviks' Central Committee from 1917 were killed, following grotesque and absurd show trials in which the accused were forced to confess to crimes they had never committed. They were tarred with the terrible accusation of being in league with Trotsky, who was in turn supposedly a fascist agent (ludicrous on several levels, not least because he was Jewish).

One of the strengths of Cliff's account of the trials is his explanation of their material basis. They weren't simply the excesses of a crazed dictator, but had important political motives and served the Stalinist bureaucracy's need, as the head of a state capitalist society, for the eradication of any threats to its own economic and political power. Cliff also looks at the degradation of the revolution and the rising power of the bureacracy to account for how once-heroic revolutionaries could abase themselves so pitifully before Stalinist power.

Cliff's account of the Moscow trials, which I'm posting here, is a chapter from the fourth and final volume of his epic Trotsky biography. This volume covers the years from Trotsky's expulsion from the Communist party in 1927 until his assassination by a Stalinist agent in Mexico in 1940.

This volume can seem bleak - these years were truly the midnight of the century, his personal suffering was immense, Trotskyism became a tiny and marginal political force - but Cliff offers a wealth of historical insight and teases out the important theoretical insights found in Trotsky's immense corpus of writing from this time.

Labels:

Soviet Union,

Stalinism,

state capitalism,

Trotsky,

Trotskyism

Friday, 21 August 2009

Building a revolutionary party

Posted item #14 'Why we need a socialist workers party'

The Socialist Review Group, which Cliff founded in 1950 after a split from the main British Trotskyist organisation, remained tiny throughout the 1950s. Entering the 1960s, it had only 60 members but grew to around 400 at the beginning of 1968 (via a name change - International Socialists - in 1962). In the wake of the tumultuous events of '68, membership was around 1000 and, following interventions in class struggle in the upturn years of the early 70s, this grew to 3-4000 by 1974.

IS changed its name to the Socialist Workers Party on New Year's Day 1977. This wasn't some momentous event, but rather a formalising of how the organisation had developed in preceding years. The party's name derived from its paper, published on a weekly basis since September 1968, and the notion of being a 'party' reflected its growth in size compared to a decade earlier.

It was also symptomatic of the emphasis Cliff placed on the goal of building a revolutionary party inspired by the example of Lenin and the Bolsheviks: 1977 was midway through the publication of Cliff's multi-volume biography of Lenin. Volume 1, called 'Building the Party', had helped persuade the great majority of IS members of the need for Leninist principles, though this was controversial with some who were still influenced by more libertarian ideas.

The article here coincided with this move from IS to SWP - Cliff doesn't attend much to the reasons for the change, but instead focuses on the tasks facing party activists. The old IS had in fact been through a rocky two or three years, with a damaging split in 1975 when around 150 members left - this was against the backdrop of a sharp change for the worse in working class combativity, disorienting everyone on the left. Cliff reflects, however, on exisiting strengths - notably the ability to take significant initiatives, e.g. Right to Work Campaign - and outlines ideas for how to move ahead.

The Socialist Review Group, which Cliff founded in 1950 after a split from the main British Trotskyist organisation, remained tiny throughout the 1950s. Entering the 1960s, it had only 60 members but grew to around 400 at the beginning of 1968 (via a name change - International Socialists - in 1962). In the wake of the tumultuous events of '68, membership was around 1000 and, following interventions in class struggle in the upturn years of the early 70s, this grew to 3-4000 by 1974.

IS changed its name to the Socialist Workers Party on New Year's Day 1977. This wasn't some momentous event, but rather a formalising of how the organisation had developed in preceding years. The party's name derived from its paper, published on a weekly basis since September 1968, and the notion of being a 'party' reflected its growth in size compared to a decade earlier.

It was also symptomatic of the emphasis Cliff placed on the goal of building a revolutionary party inspired by the example of Lenin and the Bolsheviks: 1977 was midway through the publication of Cliff's multi-volume biography of Lenin. Volume 1, called 'Building the Party', had helped persuade the great majority of IS members of the need for Leninist principles, though this was controversial with some who were still influenced by more libertarian ideas.

The article here coincided with this move from IS to SWP - Cliff doesn't attend much to the reasons for the change, but instead focuses on the tasks facing party activists. The old IS had in fact been through a rocky two or three years, with a damaging split in 1975 when around 150 members left - this was against the backdrop of a sharp change for the worse in working class combativity, disorienting everyone on the left. Cliff reflects, however, on exisiting strengths - notably the ability to take significant initiatives, e.g. Right to Work Campaign - and outlines ideas for how to move ahead.

Labels:

International Socialists,

Lenin,

revolutionary party,

SWP

Wednesday, 19 August 2009

The roots of Israel's violence

Posted item #13 'Roots of Israel's violence'

Tony Cliff wrote many articles, over a long period of time, on the subject of Palestine. This can partly be explained by personal biography - it's where he grew up, in a Jewish family during the 20s and 30s, and it was (by his own account) his disgust at the unequal treament of Arab and Jewish children that first radicalised him. His interest, though, was also sustained by recognition of historic Palestine's pivotal importance in the whole 20th century history of Western imperialism and the Middle East.

Implacable opposition to every manifestation of US imperialism was a cornerstone of Cliff's politcal outlook. In the aftermath of World War Two America unquestionably became the dominant global power - with, of course, the Soviet Union as geopolitical rival, though the US was always far more economically powerful - while Britain went into decline. The decay of the British Empire was symbolised by its humiliation in the Suez Crisis of 1956, since when the UK has consistently served as junior partner to the US.

Prior to World War Two, rival imperialisms - led by the British - carved up the Arab world for themselves. After the war it was America that took over the dominant role in this region, and ever since it has ruthlessly sought to preserve its military, polical and economic supremacy in an oil-rich and strategically vital area of the globe. The founding of Israel in 1948 -dependent on the brutal expulsion of the Palestinian people - suited American imperialist interests just fine.

For over 60 years, Israel has been a proxy aggressor for US imperialism in the Middle East, a watchdog in the Arab world. A small country reliant on vast US 'aid', it has been utterly reliable in prosecuting the wishes of the world's superpower. Cliff understood this and was an anti-Zionist in conditions much less favourable than today.

The article I'm posting here was first published in 1982, a year of renewed Israeli violence against the Palestinians, and dug into history to unearth the roots of Israel's oppression and barbarism towards those whose land it stole in the Nakba of 1948.

Tony Cliff wrote many articles, over a long period of time, on the subject of Palestine. This can partly be explained by personal biography - it's where he grew up, in a Jewish family during the 20s and 30s, and it was (by his own account) his disgust at the unequal treament of Arab and Jewish children that first radicalised him. His interest, though, was also sustained by recognition of historic Palestine's pivotal importance in the whole 20th century history of Western imperialism and the Middle East.

Implacable opposition to every manifestation of US imperialism was a cornerstone of Cliff's politcal outlook. In the aftermath of World War Two America unquestionably became the dominant global power - with, of course, the Soviet Union as geopolitical rival, though the US was always far more economically powerful - while Britain went into decline. The decay of the British Empire was symbolised by its humiliation in the Suez Crisis of 1956, since when the UK has consistently served as junior partner to the US.

Prior to World War Two, rival imperialisms - led by the British - carved up the Arab world for themselves. After the war it was America that took over the dominant role in this region, and ever since it has ruthlessly sought to preserve its military, polical and economic supremacy in an oil-rich and strategically vital area of the globe. The founding of Israel in 1948 -dependent on the brutal expulsion of the Palestinian people - suited American imperialist interests just fine.

For over 60 years, Israel has been a proxy aggressor for US imperialism in the Middle East, a watchdog in the Arab world. A small country reliant on vast US 'aid', it has been utterly reliable in prosecuting the wishes of the world's superpower. Cliff understood this and was an anti-Zionist in conditions much less favourable than today.

The article I'm posting here was first published in 1982, a year of renewed Israeli violence against the Palestinians, and dug into history to unearth the roots of Israel's oppression and barbarism towards those whose land it stole in the Nakba of 1948.

Western imperialism after WW2

A major challenge for Cliff, arriving in Britain after World War Two, was explaining the relative lack of economic depravation. While there was still poverty, it clearly wasn't a re-run of the hungry 30s, an era of mass unemployment.

A major challenge for Cliff, arriving in Britain after World War Two, was explaining the relative lack of economic depravation. While there was still poverty, it clearly wasn't a re-run of the hungry 30s, an era of mass unemployment. This was a puzzle because Trotsky, who died in 1940, had predicted a crisis for capitalism after the war. Orthodox Trotskyists assumed Trotsky must have been right so - despite the evidence of their own eyes - they clung to the belief that the system was entering, or about to enter, a crisis.

Posted item #12 'The permanent arms economy'

Cliff realised that if theory and reality don't match it must be the theory that's wrong - so he set about developing an explanation for the emerging post-war boom. Together with Michael Kidron, a young comrade in the International Socialists, he evolved an account - in the second half of the 1950s and early 60s - of postwar Western capitalism.

This account explained the boom, but also pointed to the system's underlying instability - the prosperity couldn't last forever, and at some stage there would be a return to the cycle of boom and slump. When the global economy entered recession in around 1973 Cliff and Kidron were proved absolutely right.

Their account was labelled a 'theory of permanent arms economy', as it emphasised the role of mass investment in arms production - especially from the US, by now economically dominant - in sustaining the boom. Along with the theory of state capitalism (which explained the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe) and his account of 'deflected permanent revolution' (which made sense of changes in large parts of the 'Third World'), Cliff's analysis of Western post-war society provided an overall picture of the world system.

This theoretical troika enabled IS supporters to remain firm and consistent in a politically difficult climate. The left was dominated by supporters of offical Communism or those who subscribed to reformism - at a time of stability and prosperity for Western workers, there was little opening for a revolutionary anti-capitalist alternative. But the steadfastness and patient work of IS activists in the 50s and 60s laid the basis for larger-scale poltical interventions in the crisis-ridden 70s and beyond.

Sunday, 16 August 2009

Towards women's liberation

Posted item #11 The family: haven in a heartless world?

In the early 1980s Cliff wrote a number of articles which contributed to a Marxist understanding of women's oppression and the struggle for liberation. There was a significant amount of debate about these issues within the Socialist Workers Party during the late 70s and early 80s - it took a long time to establish a clear 'party line', either theoretically or in respect of the best strategy to adopt.

It probably didn't help that the International Socialists (the SWP's forerunner) largely abstained from debates taking place in and around the women's movement that emerged in the early 70s. This arguably left the organisation in a weaker state on these important issues at a later stage. That's not to say there was no intervention in significant campaigns concerning women - struggles for better pay in the upturn of the early 70s, for example, and then an active role in the National Abortion Campaign later in the decade. But in this instance theory lagged considerably behind practice, and there was confusion about the orientation revolutionary socialists needed on the women's movement.

Cliff is admirably self-critical on this matter in his autobiography, in which he also took the sensible decision to invite Lindsey German, who has written the books 'Sex, Class and Socialism' and 'Material Girls', to contribute a brief account of the debates during this time (and how they connected with SWP activity). She rightly points out that Cliff's theoretical contributions such as articles and talks on Clara Zetkin and Alexandra Kollontai, neglected figures in the Marxist tradition, were very helpful. Above all, it was his book on 'Class Struggles and WOmen's Liberation' that contributed to revolutionaries establishing an analysis of where modern women's oppression comes from and why it persists, and also of how this can be transformed.

I'm posting here a chapter from this book. It doesn't do justice to the book as a whole, which is tremendously wide-ranging and synthesises the historical experience of struggle with some perceptive insights. It does, however, clarify Cliff's approach to the key issue of the family in capitalist society, with an impressive breadth of reference. Crucially, Cliff never loses sight of the importance of examining economic realities, whatever his focus.

In the early 1980s Cliff wrote a number of articles which contributed to a Marxist understanding of women's oppression and the struggle for liberation. There was a significant amount of debate about these issues within the Socialist Workers Party during the late 70s and early 80s - it took a long time to establish a clear 'party line', either theoretically or in respect of the best strategy to adopt.

It probably didn't help that the International Socialists (the SWP's forerunner) largely abstained from debates taking place in and around the women's movement that emerged in the early 70s. This arguably left the organisation in a weaker state on these important issues at a later stage. That's not to say there was no intervention in significant campaigns concerning women - struggles for better pay in the upturn of the early 70s, for example, and then an active role in the National Abortion Campaign later in the decade. But in this instance theory lagged considerably behind practice, and there was confusion about the orientation revolutionary socialists needed on the women's movement.

Cliff is admirably self-critical on this matter in his autobiography, in which he also took the sensible decision to invite Lindsey German, who has written the books 'Sex, Class and Socialism' and 'Material Girls', to contribute a brief account of the debates during this time (and how they connected with SWP activity). She rightly points out that Cliff's theoretical contributions such as articles and talks on Clara Zetkin and Alexandra Kollontai, neglected figures in the Marxist tradition, were very helpful. Above all, it was his book on 'Class Struggles and WOmen's Liberation' that contributed to revolutionaries establishing an analysis of where modern women's oppression comes from and why it persists, and also of how this can be transformed.

I'm posting here a chapter from this book. It doesn't do justice to the book as a whole, which is tremendously wide-ranging and synthesises the historical experience of struggle with some perceptive insights. It does, however, clarify Cliff's approach to the key issue of the family in capitalist society, with an impressive breadth of reference. Crucially, Cliff never loses sight of the importance of examining economic realities, whatever his focus.

Friday, 14 August 2009

With the workers, always...

Posted item #9 'The dead weight of the union bureaucracy'

Posted item #10 '1972: a great year for the workers'

In my previous post - an interview from 1997 - Tony Cliff discussed a range of issues as part of his reflections on 50 years of developing and building the International Socialists tradition. He didn't limit himself to a critique of the Stalinist bureaucracy, which served as the feature's starting point, but considered loosely related aspects of what it means to be an active revolutionary socialist. One of the most pertinent issues, for socialists in an advanced capitalist country like Britain, is how to relate to the leaderships of trade unions.

Cliff's insistence on always referring back to Marx's dictum that 'the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class' guided his thinking. Here he is explaining socialists' attitude to the union bureaucracies:

'Because of our theory of state capitalism we viewed socialism not from the vantage point of state ownership, but from the self-activity of the working class. This brought us back to the basic heart of Marxism. It meant that in every situation we looked to the independent activity of the rank and file.

In Britain we couldn’t fight the Stalinist bureaucracy, but in every strike we fight to keep workers independent of the trade union bureaucracy. The basic fact that we always rely on rank-and-file self-activity means that we are not demoralized when the movement goes wrong. Not every strike wins: many strikes are sold down the river by the union bureaucracy. But we are not responsible for the defeat of the strike. We argue this correctly, the right policy, the right tactics, the right strategy for workers in struggle.

In British terms, those that attach themselves to the idea of socialism from above, attach themselves to the trade union bureaucracy. They cave in to the union bureaucracy, they sell out every time they become demoralized.'

He is implicitly linking the union bureaucracy and the Labour Party - or other social democratic parties - in this passage. Conversely, rank and file struggle by workers goes together with an orientation on building revolutionary organisation. The rank and file should put pressure on the union leaders, but act indpendently where appropriate. A 'socialism from below' perspective means looking to grassroots struggles, rather than merely influencing those above - whether in Parliament or in the unions - as the means of social transformation.

Cliff's most thoroughly developed critiques of both the Labour Party's reformism and the union bureaucracy's social role were in two books co-written with his son, Donny Gluckstein: Marxism and Trade Union Struggle (about the defeated General Strike of 1926) and The Labour Party: A Marxist History. These were written in the 1980s, but he had outlined his critique of the union buraucracy much earlier, in a chapter in a 1966 book.

Co-written with Colin Barker, 'Incomes Policy, Legislation and Shop Stewards' examined - amongst other things - the relationship between shop stewards (rank and file union reps) and the well-paid full-timers above them in the union machine.

Aspects of the book will now seem like they're from another world, due to the damage to rank and file strength wrought by 30 years of neoliberalism, but the analysis of union leaders' role remains indispensable. The other item here is an inspiring article from the highest peak in the last 60 years of working class resistance: 1972. Cliff celebrates the extraordinary upsurge in militancy seen in that year, and points to workers' self-activity as the hope for future progress.

Posted item #10 '1972: a great year for the workers'

In my previous post - an interview from 1997 - Tony Cliff discussed a range of issues as part of his reflections on 50 years of developing and building the International Socialists tradition. He didn't limit himself to a critique of the Stalinist bureaucracy, which served as the feature's starting point, but considered loosely related aspects of what it means to be an active revolutionary socialist. One of the most pertinent issues, for socialists in an advanced capitalist country like Britain, is how to relate to the leaderships of trade unions.

Cliff's insistence on always referring back to Marx's dictum that 'the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class' guided his thinking. Here he is explaining socialists' attitude to the union bureaucracies:

'Because of our theory of state capitalism we viewed socialism not from the vantage point of state ownership, but from the self-activity of the working class. This brought us back to the basic heart of Marxism. It meant that in every situation we looked to the independent activity of the rank and file.

In Britain we couldn’t fight the Stalinist bureaucracy, but in every strike we fight to keep workers independent of the trade union bureaucracy. The basic fact that we always rely on rank-and-file self-activity means that we are not demoralized when the movement goes wrong. Not every strike wins: many strikes are sold down the river by the union bureaucracy. But we are not responsible for the defeat of the strike. We argue this correctly, the right policy, the right tactics, the right strategy for workers in struggle.

In British terms, those that attach themselves to the idea of socialism from above, attach themselves to the trade union bureaucracy. They cave in to the union bureaucracy, they sell out every time they become demoralized.'

He is implicitly linking the union bureaucracy and the Labour Party - or other social democratic parties - in this passage. Conversely, rank and file struggle by workers goes together with an orientation on building revolutionary organisation. The rank and file should put pressure on the union leaders, but act indpendently where appropriate. A 'socialism from below' perspective means looking to grassroots struggles, rather than merely influencing those above - whether in Parliament or in the unions - as the means of social transformation.

Cliff's most thoroughly developed critiques of both the Labour Party's reformism and the union bureaucracy's social role were in two books co-written with his son, Donny Gluckstein: Marxism and Trade Union Struggle (about the defeated General Strike of 1926) and The Labour Party: A Marxist History. These were written in the 1980s, but he had outlined his critique of the union buraucracy much earlier, in a chapter in a 1966 book.

Co-written with Colin Barker, 'Incomes Policy, Legislation and Shop Stewards' examined - amongst other things - the relationship between shop stewards (rank and file union reps) and the well-paid full-timers above them in the union machine.

Aspects of the book will now seem like they're from another world, due to the damage to rank and file strength wrought by 30 years of neoliberalism, but the analysis of union leaders' role remains indispensable. The other item here is an inspiring article from the highest peak in the last 60 years of working class resistance: 1972. Cliff celebrates the extraordinary upsurge in militancy seen in that year, and points to workers' self-activity as the hope for future progress.

Trotskyism after Trotsky

Posted item #8 Interview: 50 years of the International Socialist tradition

Tony Cliff's vital theoretical breakthrough was in the late 1940s, when he developed a theory of the Soviet Union, and its sattelite states in Eastern Europe, as state capitalist. This required a break form the dominant analysis in the Trotskyist movement internationally, which was riven with confusion about how to understand Stalinism. He was forced out of the British Trotskyist organisation of the time, along with those who agreed with him, and had to found, in 1950, an initially tiny independent group which took its name from the publication it produced: Socialist Review.

Cliff, however, viewed his work - theoretically and practically - as continuing the authentic Marxist tradition represented by Marx, Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin, Trotsky and many lesser names. He had to start small with the Socialist Review Group, but this was preferable to staying with a moribund organisation that had lost its way. Considerable far-sightedness and determination was required to pursue this course of action.

The interview posted here was conducted in 1997, half a century after Cliff first speculated that the so-called Communist countries might in fact be a version of capitalism, but one where the state essentially took the role of employer, where in the absence of competition between private firms there was nevertheless fierce competition - economically and militarally - with rival states.

Tony Cliff's vital theoretical breakthrough was in the late 1940s, when he developed a theory of the Soviet Union, and its sattelite states in Eastern Europe, as state capitalist. This required a break form the dominant analysis in the Trotskyist movement internationally, which was riven with confusion about how to understand Stalinism. He was forced out of the British Trotskyist organisation of the time, along with those who agreed with him, and had to found, in 1950, an initially tiny independent group which took its name from the publication it produced: Socialist Review.

Cliff, however, viewed his work - theoretically and practically - as continuing the authentic Marxist tradition represented by Marx, Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin, Trotsky and many lesser names. He had to start small with the Socialist Review Group, but this was preferable to staying with a moribund organisation that had lost its way. Considerable far-sightedness and determination was required to pursue this course of action.

The interview posted here was conducted in 1997, half a century after Cliff first speculated that the so-called Communist countries might in fact be a version of capitalism, but one where the state essentially took the role of employer, where in the absence of competition between private firms there was nevertheless fierce competition - economically and militarally - with rival states.

Thursday, 13 August 2009

Tony Cliff: selecting and searching

I thought I'd point out a few things you will find on this blog. In the right sidebar I've put various items I regard as valuable components in any Cliff archive. There's all 3 parts of the 1996 talk on Lenin (complete with wittily edited animations), which I've commented on previously.

You will find a number of articles about Cliff that I think capture very important elements of his poltical character and ideas - I've commented already on the John Rees tribute, but I also recommend the Paul Foot and David Renton articles. Ian Birchall's reflections on researching his biography of Cliff are also there - this paper was the inspiration for my previous post - and I've included his excellent article on Cliff in 1968 too.

I've included a small selection of Cliff's writings, courtesy of the Marxists Internet Archive which now has a mass of Cliff material. I've mainly picked fairly short pieces and they are all, I think, particularly good in different ways. They are essentially the pieces I'm posting here, and commenting on, but of course I haven't got round to all of them yet!

There are also guides to searching further, including the most exhaustive bibliography available (prepared by Ian Birchall in the early days of working on the as yet unpublished biography). The material archive - including various papers unearthed in Cliff's home after he died - are held at Warwick University, but the online archive at MIA is the next best thing.

You will find a number of articles about Cliff that I think capture very important elements of his poltical character and ideas - I've commented already on the John Rees tribute, but I also recommend the Paul Foot and David Renton articles. Ian Birchall's reflections on researching his biography of Cliff are also there - this paper was the inspiration for my previous post - and I've included his excellent article on Cliff in 1968 too.

I've included a small selection of Cliff's writings, courtesy of the Marxists Internet Archive which now has a mass of Cliff material. I've mainly picked fairly short pieces and they are all, I think, particularly good in different ways. They are essentially the pieces I'm posting here, and commenting on, but of course I haven't got round to all of them yet!

There are also guides to searching further, including the most exhaustive bibliography available (prepared by Ian Birchall in the early days of working on the as yet unpublished biography). The material archive - including various papers unearthed in Cliff's home after he died - are held at Warwick University, but the online archive at MIA is the next best thing.

Monday, 10 August 2009

5 things I never knew about Tony Cliff

I've read a great deal of Cliff's work over the years, including his own autobiography, and most of what others have written about him. However, Ian Birchall's paper about researching Cliff's life story for his biography (not yet published) unearthed some information that was new to me.

I've read a great deal of Cliff's work over the years, including his own autobiography, and most of what others have written about him. However, Ian Birchall's paper about researching Cliff's life story for his biography (not yet published) unearthed some information that was new to me. 1. Annie Machon, a former MI5 agent, was responsible for tapping Cliff's phone calls until 1996. She apparently refers to this in her 2005 book 'Spies, Lies and Whistleblowers'.

2. Cliff wrote, but abandoned, 2 books in the mid-1960s: on Keynes and the collectivisation of agriculture. These were found amongst his numerous papers after his death and are now part of the archive held at Warwick University.

3. He attended a Montessori school, providing what might be regarded as a 'progressive' education, as a child.

4. In the mid-1920s Cliff's father's building firm went bankrupt (Ian Birchall suggests this helped him become aware of capitalism's fragility).

5. The Korean war was the pretext for the expulsion, by leader Gerry Healy, of Cliff's comrades from the British section of the Trotskyist Fourth International - who went on to form the Socialist Review Group with Cliff. This group refused to support either side in this not-so-cold episode in the Cold War, in line with the 'Neither Washington nor Moscow, but international socialism' stance they later became known for.

By the way, the picture is from the 1940s: Cliff with his wife Chanie Rosenberg, who remains an active revolutionary socialist over 60 years later.

The 1970 talk about Lenin

Posted item #7 Cliff speaks on Lenin (1970)

This is the first section of Cliff's talk about Lenin from 1970. He was then in the early days of rediscovering Lenin's ideas and writings for his comrades in the International Socialists. During the first half of the 1970s he gave talks and wrote numerous articles about various aspects of Lenin's life and politics, with a major emphasis on Lenin's ideas about building a revolutionary party (and the practical experience of the Bolsheviks).

This focus was linked to his dedication to orienting the IS - which in 1970 still had a fairly weak worker composition, depending heavily on students - on working class struggles and creating a party rooted in both the Marxist tradition and working class organisations. There was some resistance to this, with Cliff having to argue relentlessly for some Leninist positions.

The talks and articles of the early 70s developed into the multi-volume Lenin biography, published between 1975 and 1979, that I wrote about in my previous post. In these books Cliff elaborates the ideas he derived from Lenin - as well as the facts of Lenin's political life - in far greater detail.

Saturday, 8 August 2009

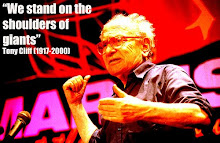

The revolutionary tradition: standing on the shoulders of giants

All four volumes of Tony Cliff's biography of Trotsky are now online, at the Marxists' Internet Archive, as well as two volumes of his Lenin biography. This is a major advance in getting Cliff's work online, so a big thank you to those involved. And thanks to the Histomatist blog for alerting me to the news, in the post 'Tony Cliff on Lenin and Trotsky'.

There's a useful chapter about the writing of these biographies in Cliff's memoir, 'A World to Win'. He comments that volume 1, 'Building the Party', is the cornerstone of the Lenin biography. It is basically the nearest you'll get to a definitive manual on building a revolutionary party. Not, it ought to be stressed, because any of us can mechanically apply what the Bolsheviks did in pre-1917 Russia in radically different conditions. Cliff recognised the differences required, but he was also exceptional at identifying the general lessons that could be derived from Lenin's experiences in taking the Bolsheviks from small underground circle to leadership of the only successful workers' revolution in history.

Cliff also suggested that it is the final volume, covering the dark years 1927 (expulsion from the Communist Party) to 1940 (assassination by a Stalinist agent), that was most important in his Trotsky biography. This was partly because it was unique in being the only volume of either biography to cover years Cliff had personal recollection of. He became a Marxist in British-ruled Palestine in around 1933 and was a dedicated Trotskyist - admittedly in a tiny group on the fringes of the Trotskyist movement to begin with - from the mid-1930s.

He also felt especially strongly about the book - titled, poetically, 'The Darker the Night, the Brighter the Star' - because he admired immensely the courage and resilience shown by Trotsky in these years, and felt pity and sorrow when contemplating what he endured. It is a powerful personal tribute - to someone who sustained himself and his political commitment through Nazism and Stalinism - as well as an acute political analysis. These were the years of - to cite just one important area - Trotsky's astute analysis of the rise of Hitler to power in Germany, which Cliff regarded as amongst the greatest of Trotsky's contributions to the Marxist tradition.

Lenin volume 1 was surely also very personally relevant - indeed I've heard it suggested that many passages could easily be interpreted as autobiography, as Cliff is to an extent writing about his efforts (in the early to mid 70s) to build revolutionary organisation through the International Socialists (which became the SWP on 1 January 1977). His own preocupation with turning IS into a disciplined, cohesive revolutionary party was the motor behind his devouring of Lenin's work - and, furthermore, writing a multi-volume biography - from 1968 onwards. His very short piece on democratic centralism in summer 1968 effectively marked the beginning of a massive study of the Bolsheviks, and also the start of a determined effort to re-orient what was then the International Socialists.

The Lenin biography was completed by the end of the 1970s and for generations of SWP members it served as a valuable guide to a hugely important era in revolutionary history and a source of insight into party building, the nature of revolution, and some knotty questions around Leninism and the common charge that the seeds of Stalinism could be found in the Bolshevik Party. The biography, published during the Cold War, was a superb refutation of precisely that charge.

The Trotsky biography came later, between 1988 and 1993. Cliff acknowledged in his memoir that he'd rather not have had the time to write either biography. It was the onset of the downturn in the mid-1970s that facilitated the Lenin biography - such a task would have been impossible in the heady days of revolt in the late 60s and early 70s. Likewise he could only devote such time to Trotsky because of the relatively low levels of resistance and struggle during the period in which wrote it, though he always took an active interest in contemporary politcs and day-to-day party building.

It was appropriate that the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union collapse during this latter period: events that vindicated Cliff's pioneering analysis of forty years earlier, and which created an opening for the rediscovery of the tradition of which Trotsky was such a magnificent representative.

That tradition was a world away from the monstrosities of Stalinism. It was, and is, a tradition of socialism from below, with the self-activity of the working class at its core. Today, with capitalism in its deepest crisis since Trotsky's final struggle (and Cliff's formative years), the need for us to carry forward that thread of genuine socialism is profound. The biographies of Lenin and Trotsky are an aid to us in the project of strengthening revolutionary socialism in the 21st century.

A full index of Cliff's online writings - including the biographies - can be found here: www.marxists.org/archive/cliff/

Thursday, 6 August 2009

Cliff on Lenin

Posted item #6 Cliff speaks on Lenin and the party (1996)

Marxism 96 appears to be the source of a great deal of the publicly available video and audio material of Tony Cliff: the only video interview with Cliff, the only video on YouTube featuring Cliff's public speaking, and also this audio recording (in 3 parts) of his talk on Lenin. If he'd been laid low with flu that week, we would have almost nothing.

I've already posted the videos - this one is strictly speaking audio, but it has enjoyable animation to accompany it (courtesy of notthebbc on YouTube). The three parts of the talk together provide most of the key Leninist principles Cliff championed, especially from the 1970s onwards. He returned, again and again, to the core concepts outlined here, often using the same examples and phrases to make his point.

His bit, at the end of Part 1, on how revolutionaries relate to other workers on a picket line crystallises the major issues around how the revolutionary left can contribute to achieving shared goals and simultaneously win wider support for their ideas in the working class. This was one of the recurring preoccupations of Cliff's life, in particular once his group had reached a size where it could have influence on the course of at least some struggles. This was true from probably the early 1970s onwards.

By 1996 the Socialist Workers Party had somewhere between 8000 and 10,000 members, many of them with roots in the trade union movement and many possessing political expertise gained from years of activism. Cliff was insistent on the need for every generation of revolutionaries to learn from the giants of our tradition. This talk offers an example of him, approaching 80, popularising the ideas and spirit of one of those giants for a new generation.

Cliff on revolution, democracy and socialism

Posted item #5 Democratic revolution or socialist revolution?

As I noted in an earlier post, the key principle of Marxism for Cliff was always: the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class itself. Socialism and human liberation cannot be legislated by well-meaning reformers, fought for by guerilla revolutionaries, or imposed by the gun or the bomb. Cliff rejected the notion that the Soviet Union was socialist - he saw that it was state capitalist, with a different form of capitalism to the Western variants but capitalist nonetheless: driven by economic and military competition (primarily with the US), divided into classes, and reliant upon exploitation of workers. It can't have been a workers' state because the workers clearly had no control over their own economy or society.

Similarly, the Communist states established in Eastern Europe after 1945 were top-down regimes, in which democracy was absent. It made a mockery of socialist principles to suggest they had anything in common with genuine socialism. They had been achieved without any grassroots workers' struggles, without revolution. Where, then, was the self-emancipation of the working class?

He analysed Mao's regime in China from the same point of view and - controversially on the left - rejected the idea that Castro's Cuba could be regarded as socialist. Democracy was and is the heart of the revolutionary socialist tradition.

By emphasising this fundamental principle, and testing the claims of states to 'socialism' against this criterion, Cliff recovered the thread of 'socialism from below' - the lineage of Marx, Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky - from the travesty of Stalinism. He played a key role in renewing the classical Marxist tradition - in theory and in practice - for new generations.

The chapter from Marxism at the Millennium - a short book published shortly before Cliff's death - I'm posting here is a re-statement of Cliff's ideas about the relationship between democracy and socialism. It recognises the severe limits placed on democracy by capitalist society. For him, the thwarted democracy we have in modern capitalist societies is a poor deal - real democracy is radically different, and depends upon economic control by the working class.

From this perspective the question of what a revolution's aims are becomes hugely important. A revolutionary movement that aims only for political democracy and power is doomed to perpetuate the injustices and miseries of capitalism. The alternative is the kind of radical economic democracy associated with the early period of Russian revolutionary government after October 1917. Though revolution tends to seem distant for us, this issue has in fact recurred, in many parts of the world, ever since the Russian Revolution.

In a world as unstable, violent and crisis-ridden as ours, there are sure to be more revolutionary upheavals and democratic upsurges. Learning the lessons of history is essential in determining what it means - in practice - to be a revolutionary in the 21st century.

As I noted in an earlier post, the key principle of Marxism for Cliff was always: the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class itself. Socialism and human liberation cannot be legislated by well-meaning reformers, fought for by guerilla revolutionaries, or imposed by the gun or the bomb. Cliff rejected the notion that the Soviet Union was socialist - he saw that it was state capitalist, with a different form of capitalism to the Western variants but capitalist nonetheless: driven by economic and military competition (primarily with the US), divided into classes, and reliant upon exploitation of workers. It can't have been a workers' state because the workers clearly had no control over their own economy or society.

Similarly, the Communist states established in Eastern Europe after 1945 were top-down regimes, in which democracy was absent. It made a mockery of socialist principles to suggest they had anything in common with genuine socialism. They had been achieved without any grassroots workers' struggles, without revolution. Where, then, was the self-emancipation of the working class?

He analysed Mao's regime in China from the same point of view and - controversially on the left - rejected the idea that Castro's Cuba could be regarded as socialist. Democracy was and is the heart of the revolutionary socialist tradition.

By emphasising this fundamental principle, and testing the claims of states to 'socialism' against this criterion, Cliff recovered the thread of 'socialism from below' - the lineage of Marx, Engels, Luxemburg, Lenin and Trotsky - from the travesty of Stalinism. He played a key role in renewing the classical Marxist tradition - in theory and in practice - for new generations.

The chapter from Marxism at the Millennium - a short book published shortly before Cliff's death - I'm posting here is a re-statement of Cliff's ideas about the relationship between democracy and socialism. It recognises the severe limits placed on democracy by capitalist society. For him, the thwarted democracy we have in modern capitalist societies is a poor deal - real democracy is radically different, and depends upon economic control by the working class.

From this perspective the question of what a revolution's aims are becomes hugely important. A revolutionary movement that aims only for political democracy and power is doomed to perpetuate the injustices and miseries of capitalism. The alternative is the kind of radical economic democracy associated with the early period of Russian revolutionary government after October 1917. Though revolution tends to seem distant for us, this issue has in fact recurred, in many parts of the world, ever since the Russian Revolution.

In a world as unstable, violent and crisis-ridden as ours, there are sure to be more revolutionary upheavals and democratic upsurges. Learning the lessons of history is essential in determining what it means - in practice - to be a revolutionary in the 21st century.

Labels:

China,

Cuba,

democracy,

Eastern Europe,

revolution,

socialism,

Soviet Union

Tuesday, 4 August 2009

Video footage of Cliff from Marxism 96

This film about the 1996 Marxism event in London features Cliff alongside fellow speakers like Tony Benn, Paul Foot, Seumas Milne and John Pilger. The excerpts of Cliff speaking are from 00.35 onwards. This film was made at the same time as the video interview with Cliff, which I posted previously (a few clips from that interview are included here). Sadly these are the only film recordings of Cliff you will find anywhere on the 'Net, though thankfully there's some good audio recordings of Cliff talking about Lenin and the revolutionary party to be found on YouTube (I'll feature these in later posts).

Determination and flexibility

After Cliff's death in April 2000, a tribute called 'Tony Cliff: theory and practice' reflected on the qualities that enabled Cliff to provide effective leadership in the International Socialists tradition over half a century. Writing in the International Socialism journal, of which he was then editor, John Rees described Cliff as 'the most determined person I have ever met'. His single-mindedness and unwavering commitment to revolutionary socialism, which Dave Renton also captures in his tribute, were phenomenal.

After Cliff's death in April 2000, a tribute called 'Tony Cliff: theory and practice' reflected on the qualities that enabled Cliff to provide effective leadership in the International Socialists tradition over half a century. Writing in the International Socialism journal, of which he was then editor, John Rees described Cliff as 'the most determined person I have ever met'. His single-mindedness and unwavering commitment to revolutionary socialism, which Dave Renton also captures in his tribute, were phenomenal.A key aspect of this was his determination to pursue a course of action 100%. As Rees observes, it is only possible to assess any strategy or intervention if it has been done properly. After all, if it was only done with 50% effort and failed then how can you tell if it was the wrong strategy, or simply not done with enough dedication? This means it isn't sufficient to simply pick up and drop initiatives without any commitment to seeing things through.

I recall Cliff imploring us at a SWP meeting in the late 1990s, "Don't be grasshoppers, just jumping from one thing to the next thing". He was partly championing consistency and commitment, but he also meant that socialist activists mustn't intervene in various activities and struggles without also building socialist organisation. Strengthening the revolutionary party helps build bigger and more effective campaigns in future, and also increases the forces of revolutionary socialism.

Another key element was ruthless honesty - not as a moral injunction but in order to evaluate situations accurately and plot a course of action. Cliff repeatedly insisted that revolutionaries must not tell lies, either to others or to themselves. Telling the truth to yourself - seeing the world accurately, facing reality - is an underrated quality. The alternative is a distorted view that prevents us deciding on the correct approach. Such honesty was crucial in Cliff's development of the theory of state capitlaism to understand the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in the late 1940s. He recognised that orthodox Trotskyist claims just didn't match reality, which prompted his challenge to the received wisdom.

The flipside of Cliff's determination and decisiveness was flexibility. While being unshakeable in principle, he had a gift for adapting tactics and methods of organising to suit changing circumstances. There will inevitably be occasional tactical errors, and it may take time to convince everyone of the need for change, but it is vital to grasp the key tasks for socialists at any given time and adapt accordingly. In this respect he was influenced by Lenin, who made massive tactical turns in repsonse to the pressures of events, especially in the revolutionary year of 1917 but to an extent throughout the Bolsheviks' history.

This combination of dedication, decisiveness, honesty and adaptability is necessary now, as ever, for socialists. Responding to the greatest crisis of capitalism for decades requires initative - and then commitment to seeing it through. It also means adapting how revolutionaries organise to fit changed conditions, whether that's the kind of meetings we organise, the alliances we form or the ways we use new technologies to spread resistance and disseminate ideas.

Sunday, 2 August 2009

Nothing so romantic

Posted item #4 'Nothing so romantic'

This classic interview from 1970 provides insight into the times as well as some illuminating examples of Cliff's political positions and preoccupations. He stresses 'the statement that the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class'. This distinguished the IS tradition from not only reformism but also Stalinism and its variants - Maoism was still fashionable on the left at the time, while many revolutionaries romanticised Third World struggles at the same time as despairing of Western working classes.

Cliff repeatedly insisted there can be no substitutes for mass working class struggle, no convenient shortcuts. This helped distinguish IS in late 60s and early 70s - from Labour and the Communist Party, yes, but also from many who considered themselves revolutionaries.

He acknowledges that IS at the time didn't yet have a strong enough base in the manual working class - admirable honesty (typical of Cliff), especially as he was addressing a largely non-IS audience. The high student representation in IS was mainly a symptom of the organisation's highly successful work in the universities in 1967-68.

Over the next few years - a period of upturn in working class struggle - IS did indeed orient sharply on building amongst (and recruiting) workers. By 1974 membership was 3-4000, up from 1000 at the end of 1968, and Socialist Worker was a 16-page weekly with a circulation that stretched far beyond the membership of IS. The paper, together with great energy being devoted to rank and file initiatives in industry, enabled the organisation to implant serious roots in the organised working class.

This classic interview from 1970 provides insight into the times as well as some illuminating examples of Cliff's political positions and preoccupations. He stresses 'the statement that the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class'. This distinguished the IS tradition from not only reformism but also Stalinism and its variants - Maoism was still fashionable on the left at the time, while many revolutionaries romanticised Third World struggles at the same time as despairing of Western working classes.

Cliff repeatedly insisted there can be no substitutes for mass working class struggle, no convenient shortcuts. This helped distinguish IS in late 60s and early 70s - from Labour and the Communist Party, yes, but also from many who considered themselves revolutionaries.

He acknowledges that IS at the time didn't yet have a strong enough base in the manual working class - admirable honesty (typical of Cliff), especially as he was addressing a largely non-IS audience. The high student representation in IS was mainly a symptom of the organisation's highly successful work in the universities in 1967-68.

Over the next few years - a period of upturn in working class struggle - IS did indeed orient sharply on building amongst (and recruiting) workers. By 1974 membership was 3-4000, up from 1000 at the end of 1968, and Socialist Worker was a 16-page weekly with a circulation that stretched far beyond the membership of IS. The paper, together with great energy being devoted to rank and file initiatives in industry, enabled the organisation to implant serious roots in the organised working class.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)