Posted item #9 'The dead weight of the union bureaucracy'

Posted item #10 '1972: a great year for the workers'

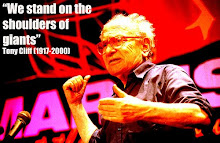

In my previous post - an interview from 1997 - Tony Cliff discussed a range of issues as part of his reflections on 50 years of developing and building the International Socialists tradition. He didn't limit himself to a critique of the Stalinist bureaucracy, which served as the feature's starting point, but considered loosely related aspects of what it means to be an active revolutionary socialist. One of the most pertinent issues, for socialists in an advanced capitalist country like Britain, is how to relate to the leaderships of trade unions.

Cliff's insistence on always referring back to Marx's dictum that 'the emancipation of the working class is the act of the working class' guided his thinking. Here he is explaining socialists' attitude to the union bureaucracies:

'Because of our theory of state capitalism we viewed socialism not from the vantage point of state ownership, but from the self-activity of the working class. This brought us back to the basic heart of Marxism. It meant that in every situation we looked to the independent activity of the rank and file.

In Britain we couldn’t fight the Stalinist bureaucracy, but in every strike we fight to keep workers independent of the trade union bureaucracy. The basic fact that we always rely on rank-and-file self-activity means that we are not demoralized when the movement goes wrong. Not every strike wins: many strikes are sold down the river by the union bureaucracy. But we are not responsible for the defeat of the strike. We argue this correctly, the right policy, the right tactics, the right strategy for workers in struggle.

In British terms, those that attach themselves to the idea of socialism from above, attach themselves to the trade union bureaucracy. They cave in to the union bureaucracy, they sell out every time they become demoralized.'

He is implicitly linking the union bureaucracy and the Labour Party - or other social democratic parties - in this passage. Conversely, rank and file struggle by workers goes together with an orientation on building revolutionary organisation. The rank and file should put pressure on the union leaders, but act indpendently where appropriate. A 'socialism from below' perspective means looking to grassroots struggles, rather than merely influencing those above - whether in Parliament or in the unions - as the means of social transformation.

Cliff's most thoroughly developed critiques of both the Labour Party's reformism and the union bureaucracy's social role were in two books co-written with his son, Donny Gluckstein: Marxism and Trade Union Struggle (about the defeated General Strike of 1926) and The Labour Party: A Marxist History. These were written in the 1980s, but he had outlined his critique of the union buraucracy much earlier, in a chapter in a 1966 book.

Co-written with Colin Barker, 'Incomes Policy, Legislation and Shop Stewards' examined - amongst other things - the relationship between shop stewards (rank and file union reps) and the well-paid full-timers above them in the union machine.

Aspects of the book will now seem like they're from another world, due to the damage to rank and file strength wrought by 30 years of neoliberalism, but the analysis of union leaders' role remains indispensable. The other item here is an inspiring article from the highest peak in the last 60 years of working class resistance: 1972. Cliff celebrates the extraordinary upsurge in militancy seen in that year, and points to workers' self-activity as the hope for future progress.

Friday, 14 August 2009

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment