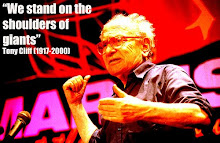

I started this blog on 25 July - less than six weeks ago - as a brief summer project. My aim was to collate a selection of Tony Cliff's most relevant and interesting writings, supported by a modest amount of video and audio input (there's sadly not much available), with my own introductions and commentaries.

I'm pleased to have covered a wide range of topics. Hopefully my own commentaries are useful, and readers are able to infer contemporary implications for themselves. Most importantly, I highly recommend reading the Cliff articles and book chapters I've posted over recent weeks - and indeed it's worth digging further into the archive of his work. There are now well over 100 items in the Cliff index on the Marxists Internet Archive.

In the right sidebar of this blog you'll find a list of the specific pieces of Cliff's writing I've posted, plus examples of Cliff speaking, articles about him and ways of exploring further. These features should serve as a guide - together with the blog posts - to a great revolutionary socialist from whom we can continue to learn an enormous amount.

Finally, I should mention an earlier request for examples of Cliff's rhetoric - stories, metaphors, analogies, jokes - which I wanted to collect. Instead of posting them here, as planned, I've decided to feature a selection of them on my regular Luna17 blog - http://luna17activist.blogspot.com - as soon as I get round to it.

So, please use this archive as a theoretical resource, a tool in both understanding society and changing it. It is no academic exercise - as Marx noted, philosophers have interpreted the world but the point is to change it. For, as Marx also wrote, we have a world to win.

Wednesday, 2 September 2009

Thursday, 27 August 2009

Towards a revolutionary party

My previous post concerned Socialist Worker, especially in the upturn years of 1968-74, as an illustration of the role of a newspaper in building socialist organisation. This included my final link to one of Tony Cliff's own articles, but I think it's also useful to read Ian Birchall's account of this period. There's a great deal of overlap with Cliff's 1974 article about Socialist Worker; as a historical summary, focusing especially on how the International Socialists (forerunner of the Socialist Workers Party) responded to the times, it provides all the relevant background.

As well as illuminating this hugely important era in the history of the left and the working class movement in Britain, Birchall's essay also offers some fascinating insights into how a revolutionary socialist organisation can grow. IS had 400+ members at the start of 1968; by 1974 it had over 3000. There was no weekly paper at the start of 1968; by 1974 a 16-page weekly Socialist Worker peaked at a circulation of 40,000. The journey was uneven and dotted with obstacles, but it remains a superb achievement for such a small group to make so much of the possibilities - and reap the benefits.

As well as illuminating this hugely important era in the history of the left and the working class movement in Britain, Birchall's essay also offers some fascinating insights into how a revolutionary socialist organisation can grow. IS had 400+ members at the start of 1968; by 1974 it had over 3000. There was no weekly paper at the start of 1968; by 1974 a 16-page weekly Socialist Worker peaked at a circulation of 40,000. The journey was uneven and dotted with obstacles, but it remains a superb achievement for such a small group to make so much of the possibilities - and reap the benefits.

Wednesday, 26 August 2009

The revolutionary paper as organiser

Posted item #16 'The use of Socialist Worker as an organiser'

This is the final example of Cliff's writing that I am posting. Looking back over this blog, as it's developed during the last few weeks, I'm conscious of the wide range of topics covered. However, even this range doesn't fully reflect the breadth of Cliff's political expertise, which can be more fully grasped by referring to the Cliff index on the Marxists Internet Archive.

This is an appropriate place to conclude the archive of Cliff's own work: an article about the revolutionary paper, one of Cliff's abiding preoccupations. The paper was central to his conception of a revolutionary party and its work, a commitment inherited directly from Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who famously published Pravda (a daily paper launched in 1912).

The article's title sums up the newspaper's political significance for Cliff, as for Lenin: not merely propaganda, the paper serves practical organisation by revolutionary socialists. It is published by the party and is accountable to it. It is, above all, a method for creating networks of socialists, and furthermore enabling those organised socialists to connect with wider layers of sympathisers and supporters.

Cliff took from his knowledge of Pravda, which he wrote about in the first volume of his Lenin biography (published in 1975), the notion of a workers' paper not just a paper for workers, i.e. workers must have a sense of ownership of the paper, which derives from it being partly composed of workers' own contributions and also from selling the paper. When someone moves from buying to selling a publication something important changes - they identify themselves with it, and with its political ideas and the organisation created through its networks.

Socialist Worker was launched as a weekly in September 1968 (previously there had been a monthly paper). It was just a scruffy 4 pages, but this increased to 6, then 8, then 12, and finally 16 pages by 1972. This rapid growth in the paper's size, during just a few years, was accompanied by similarly rapid growth in circulation. In 1972 the International Socialists (IS) only had between 2000 and 3000 members, yet the paper's circulation was around 30,000, providing the relatively small organisation with a wide periphery.

Sales are thought to have peaked in 1974, with circulation reaching 40,000, on the back of a period of upturn in working class combativity and struggle. This article was published in April 1974, when socialists and the labour movement were still riding high on the crest of the wave of workers' militancy, in an internal bulletin for members of IS.

This is the final example of Cliff's writing that I am posting. Looking back over this blog, as it's developed during the last few weeks, I'm conscious of the wide range of topics covered. However, even this range doesn't fully reflect the breadth of Cliff's political expertise, which can be more fully grasped by referring to the Cliff index on the Marxists Internet Archive.

This is an appropriate place to conclude the archive of Cliff's own work: an article about the revolutionary paper, one of Cliff's abiding preoccupations. The paper was central to his conception of a revolutionary party and its work, a commitment inherited directly from Lenin and the Bolsheviks, who famously published Pravda (a daily paper launched in 1912).

The article's title sums up the newspaper's political significance for Cliff, as for Lenin: not merely propaganda, the paper serves practical organisation by revolutionary socialists. It is published by the party and is accountable to it. It is, above all, a method for creating networks of socialists, and furthermore enabling those organised socialists to connect with wider layers of sympathisers and supporters.

Cliff took from his knowledge of Pravda, which he wrote about in the first volume of his Lenin biography (published in 1975), the notion of a workers' paper not just a paper for workers, i.e. workers must have a sense of ownership of the paper, which derives from it being partly composed of workers' own contributions and also from selling the paper. When someone moves from buying to selling a publication something important changes - they identify themselves with it, and with its political ideas and the organisation created through its networks.

Socialist Worker was launched as a weekly in September 1968 (previously there had been a monthly paper). It was just a scruffy 4 pages, but this increased to 6, then 8, then 12, and finally 16 pages by 1972. This rapid growth in the paper's size, during just a few years, was accompanied by similarly rapid growth in circulation. In 1972 the International Socialists (IS) only had between 2000 and 3000 members, yet the paper's circulation was around 30,000, providing the relatively small organisation with a wide periphery.

Sales are thought to have peaked in 1974, with circulation reaching 40,000, on the back of a period of upturn in working class combativity and struggle. This article was published in April 1974, when socialists and the labour movement were still riding high on the crest of the wave of workers' militancy, in an internal bulletin for members of IS.

Monday, 24 August 2009

Midnight of the century

Posted item #15 'The Moscow Trials'

The 1930s were turbulent times and witnessed the historic defeat of the working class in two hugely important ways: the rise of fascism and the entrenchment of Stalinism in the Soviet Union. The triumph of Hitler's Nazis in 1933 represented a crushing defeat for the powerful German working class, while the consolidation of Stalin's power crushed the hopes of 1917 and nearly extinguished the authentic marxist tradition.

Trotsky, more than anyone, carried the torch of genuine revolutionary socialism forwards. He did this in extraordinarily harsh and brutal conditions, for himself personally and for his supporters.

Many of Trotsky's 1930s writing exemplify the best in the marxist tradition - for example his analysis of the events in Germany - and he strove to continue revolutionary organisation, despite awful repression in the Soviet Union (from where he was exiled in 1929) and being so marginalised everywhere.

The Moscow Trials of 1935-37 symbolise how far Stalin's counter-revolution had gone, how utterly removed from the revolutionary aspirations of the post-1917 period his regime had become. Many of the Bolsheviks' Central Committee from 1917 were killed, following grotesque and absurd show trials in which the accused were forced to confess to crimes they had never committed. They were tarred with the terrible accusation of being in league with Trotsky, who was in turn supposedly a fascist agent (ludicrous on several levels, not least because he was Jewish).

One of the strengths of Cliff's account of the trials is his explanation of their material basis. They weren't simply the excesses of a crazed dictator, but had important political motives and served the Stalinist bureaucracy's need, as the head of a state capitalist society, for the eradication of any threats to its own economic and political power. Cliff also looks at the degradation of the revolution and the rising power of the bureacracy to account for how once-heroic revolutionaries could abase themselves so pitifully before Stalinist power.

Cliff's account of the Moscow trials, which I'm posting here, is a chapter from the fourth and final volume of his epic Trotsky biography. This volume covers the years from Trotsky's expulsion from the Communist party in 1927 until his assassination by a Stalinist agent in Mexico in 1940.

This volume can seem bleak - these years were truly the midnight of the century, his personal suffering was immense, Trotskyism became a tiny and marginal political force - but Cliff offers a wealth of historical insight and teases out the important theoretical insights found in Trotsky's immense corpus of writing from this time.

Labels:

Soviet Union,

Stalinism,

state capitalism,

Trotsky,

Trotskyism

Friday, 21 August 2009

Building a revolutionary party

Posted item #14 'Why we need a socialist workers party'

The Socialist Review Group, which Cliff founded in 1950 after a split from the main British Trotskyist organisation, remained tiny throughout the 1950s. Entering the 1960s, it had only 60 members but grew to around 400 at the beginning of 1968 (via a name change - International Socialists - in 1962). In the wake of the tumultuous events of '68, membership was around 1000 and, following interventions in class struggle in the upturn years of the early 70s, this grew to 3-4000 by 1974.

IS changed its name to the Socialist Workers Party on New Year's Day 1977. This wasn't some momentous event, but rather a formalising of how the organisation had developed in preceding years. The party's name derived from its paper, published on a weekly basis since September 1968, and the notion of being a 'party' reflected its growth in size compared to a decade earlier.

It was also symptomatic of the emphasis Cliff placed on the goal of building a revolutionary party inspired by the example of Lenin and the Bolsheviks: 1977 was midway through the publication of Cliff's multi-volume biography of Lenin. Volume 1, called 'Building the Party', had helped persuade the great majority of IS members of the need for Leninist principles, though this was controversial with some who were still influenced by more libertarian ideas.

The article here coincided with this move from IS to SWP - Cliff doesn't attend much to the reasons for the change, but instead focuses on the tasks facing party activists. The old IS had in fact been through a rocky two or three years, with a damaging split in 1975 when around 150 members left - this was against the backdrop of a sharp change for the worse in working class combativity, disorienting everyone on the left. Cliff reflects, however, on exisiting strengths - notably the ability to take significant initiatives, e.g. Right to Work Campaign - and outlines ideas for how to move ahead.

The Socialist Review Group, which Cliff founded in 1950 after a split from the main British Trotskyist organisation, remained tiny throughout the 1950s. Entering the 1960s, it had only 60 members but grew to around 400 at the beginning of 1968 (via a name change - International Socialists - in 1962). In the wake of the tumultuous events of '68, membership was around 1000 and, following interventions in class struggle in the upturn years of the early 70s, this grew to 3-4000 by 1974.

IS changed its name to the Socialist Workers Party on New Year's Day 1977. This wasn't some momentous event, but rather a formalising of how the organisation had developed in preceding years. The party's name derived from its paper, published on a weekly basis since September 1968, and the notion of being a 'party' reflected its growth in size compared to a decade earlier.

It was also symptomatic of the emphasis Cliff placed on the goal of building a revolutionary party inspired by the example of Lenin and the Bolsheviks: 1977 was midway through the publication of Cliff's multi-volume biography of Lenin. Volume 1, called 'Building the Party', had helped persuade the great majority of IS members of the need for Leninist principles, though this was controversial with some who were still influenced by more libertarian ideas.

The article here coincided with this move from IS to SWP - Cliff doesn't attend much to the reasons for the change, but instead focuses on the tasks facing party activists. The old IS had in fact been through a rocky two or three years, with a damaging split in 1975 when around 150 members left - this was against the backdrop of a sharp change for the worse in working class combativity, disorienting everyone on the left. Cliff reflects, however, on exisiting strengths - notably the ability to take significant initiatives, e.g. Right to Work Campaign - and outlines ideas for how to move ahead.

Labels:

International Socialists,

Lenin,

revolutionary party,

SWP

Wednesday, 19 August 2009

The roots of Israel's violence

Posted item #13 'Roots of Israel's violence'

Tony Cliff wrote many articles, over a long period of time, on the subject of Palestine. This can partly be explained by personal biography - it's where he grew up, in a Jewish family during the 20s and 30s, and it was (by his own account) his disgust at the unequal treament of Arab and Jewish children that first radicalised him. His interest, though, was also sustained by recognition of historic Palestine's pivotal importance in the whole 20th century history of Western imperialism and the Middle East.

Implacable opposition to every manifestation of US imperialism was a cornerstone of Cliff's politcal outlook. In the aftermath of World War Two America unquestionably became the dominant global power - with, of course, the Soviet Union as geopolitical rival, though the US was always far more economically powerful - while Britain went into decline. The decay of the British Empire was symbolised by its humiliation in the Suez Crisis of 1956, since when the UK has consistently served as junior partner to the US.

Prior to World War Two, rival imperialisms - led by the British - carved up the Arab world for themselves. After the war it was America that took over the dominant role in this region, and ever since it has ruthlessly sought to preserve its military, polical and economic supremacy in an oil-rich and strategically vital area of the globe. The founding of Israel in 1948 -dependent on the brutal expulsion of the Palestinian people - suited American imperialist interests just fine.

For over 60 years, Israel has been a proxy aggressor for US imperialism in the Middle East, a watchdog in the Arab world. A small country reliant on vast US 'aid', it has been utterly reliable in prosecuting the wishes of the world's superpower. Cliff understood this and was an anti-Zionist in conditions much less favourable than today.

The article I'm posting here was first published in 1982, a year of renewed Israeli violence against the Palestinians, and dug into history to unearth the roots of Israel's oppression and barbarism towards those whose land it stole in the Nakba of 1948.

Tony Cliff wrote many articles, over a long period of time, on the subject of Palestine. This can partly be explained by personal biography - it's where he grew up, in a Jewish family during the 20s and 30s, and it was (by his own account) his disgust at the unequal treament of Arab and Jewish children that first radicalised him. His interest, though, was also sustained by recognition of historic Palestine's pivotal importance in the whole 20th century history of Western imperialism and the Middle East.

Implacable opposition to every manifestation of US imperialism was a cornerstone of Cliff's politcal outlook. In the aftermath of World War Two America unquestionably became the dominant global power - with, of course, the Soviet Union as geopolitical rival, though the US was always far more economically powerful - while Britain went into decline. The decay of the British Empire was symbolised by its humiliation in the Suez Crisis of 1956, since when the UK has consistently served as junior partner to the US.

Prior to World War Two, rival imperialisms - led by the British - carved up the Arab world for themselves. After the war it was America that took over the dominant role in this region, and ever since it has ruthlessly sought to preserve its military, polical and economic supremacy in an oil-rich and strategically vital area of the globe. The founding of Israel in 1948 -dependent on the brutal expulsion of the Palestinian people - suited American imperialist interests just fine.

For over 60 years, Israel has been a proxy aggressor for US imperialism in the Middle East, a watchdog in the Arab world. A small country reliant on vast US 'aid', it has been utterly reliable in prosecuting the wishes of the world's superpower. Cliff understood this and was an anti-Zionist in conditions much less favourable than today.

The article I'm posting here was first published in 1982, a year of renewed Israeli violence against the Palestinians, and dug into history to unearth the roots of Israel's oppression and barbarism towards those whose land it stole in the Nakba of 1948.

Western imperialism after WW2

A major challenge for Cliff, arriving in Britain after World War Two, was explaining the relative lack of economic depravation. While there was still poverty, it clearly wasn't a re-run of the hungry 30s, an era of mass unemployment.

A major challenge for Cliff, arriving in Britain after World War Two, was explaining the relative lack of economic depravation. While there was still poverty, it clearly wasn't a re-run of the hungry 30s, an era of mass unemployment. This was a puzzle because Trotsky, who died in 1940, had predicted a crisis for capitalism after the war. Orthodox Trotskyists assumed Trotsky must have been right so - despite the evidence of their own eyes - they clung to the belief that the system was entering, or about to enter, a crisis.

Posted item #12 'The permanent arms economy'

Cliff realised that if theory and reality don't match it must be the theory that's wrong - so he set about developing an explanation for the emerging post-war boom. Together with Michael Kidron, a young comrade in the International Socialists, he evolved an account - in the second half of the 1950s and early 60s - of postwar Western capitalism.

This account explained the boom, but also pointed to the system's underlying instability - the prosperity couldn't last forever, and at some stage there would be a return to the cycle of boom and slump. When the global economy entered recession in around 1973 Cliff and Kidron were proved absolutely right.

Their account was labelled a 'theory of permanent arms economy', as it emphasised the role of mass investment in arms production - especially from the US, by now economically dominant - in sustaining the boom. Along with the theory of state capitalism (which explained the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe) and his account of 'deflected permanent revolution' (which made sense of changes in large parts of the 'Third World'), Cliff's analysis of Western post-war society provided an overall picture of the world system.

This theoretical troika enabled IS supporters to remain firm and consistent in a politically difficult climate. The left was dominated by supporters of offical Communism or those who subscribed to reformism - at a time of stability and prosperity for Western workers, there was little opening for a revolutionary anti-capitalist alternative. But the steadfastness and patient work of IS activists in the 50s and 60s laid the basis for larger-scale poltical interventions in the crisis-ridden 70s and beyond.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)